Tags

Food, Ingredients, M.F.K Fisher, Nonfiction, Recipes, Stories, Travel, Writing

Avram Dumitrescu

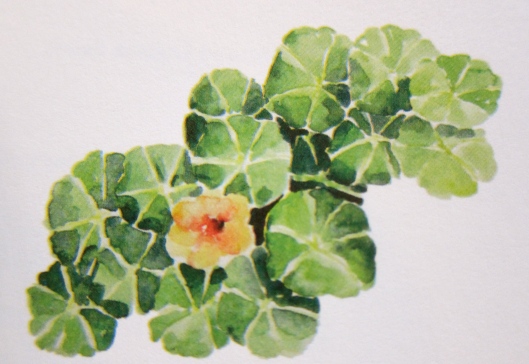

I discovered nasturtiums and the food writer M.F.K Fisher around the same time, so it seems fitting to include them both here. This recipe might also sum up Fisher’s approach to life and cooking, as it is both daring and in some senses obvious; nasturtiums grow wild, as well as being the easiest things to cultivate, and most of us have a loaf of bread knocking about. The rest is up to you.

Her life is hard to summarize without reducing it to the amount of times she moved house. She was a true vagabond, shuttling between France, Switzerland and her native California; back and forth she went like a ping-pong ball. Possibly because of this, she had a complete lack of vanity about where she cooked and with what. Some of her early, settler-influenced dishes read like one of Edward Lear’s nonsense poems – clabber custard, cocoa toast, tomato soup cake – but her message is disarmingly relevant. Eventually, we must ditch the gurus and find our own voice. Fisher herself was entirely self-taught, spurning even her French landlady’s attempts to school her in the basics. She simply made it up as she went along. The limitations of her surroundings, and the lack of equipment – in one house the radiator stood in for a stove, and in another, the cold meant she cooked wearing a fur coat and gloves – dictated what she was able to prepare, and this was what excited her most; that making do is liberating, and we are confined by choice.

She is the antidote to our learned helplessness – our need for ‘experts’ – and the champion of trial and error. She wanted us to feel our way, physically and psychically, through the food we cooked. About this, she said “I believe that through touch, or perhaps because of its agents, other senses regain their first strengths.”

A devotee of offal at a time when Miracle Whip was considered classy, and a life-long hatred of American salads sets her apart in ways that even now appear radical and eccentric. She is often described as America’s answer to Elizabeth David, but I think this is to do her a disservice. To my mind, her writing has the tough lyricism of the survivor. Flinty, resolute, economical, she was a woman raised under big skies in a brave, new world.

Nasturtium-leaf sandwiches

I know it may be controversial, championing the ‘wich in these carb-free times, but perhaps it’s due a revival. There can be nothing more satisfying than a torn hunk of baguette, with some sharp cheddar (crisps optional), or a few slivers of smoked salmon inside a thin, wheaty shell. And then there is toast, at which even the thought makes my cheeks sing, and gives butter a reason to live.

If you’re craving something cleaner, you could make a nasturtium salad; it works in much the same way as watercress, being from the Indian cress family. In fact, the word originally comes from the Latin nasus tortus, meaning “twisted nose”, supposedly because of what it does to your sinuses. Creamy clouds of pepperiness and a shock of blossom covered in the lightest of dressings is springtime in a bowl.

From With Bold Knife and Fork, M.F.K Fisher (1969)

Makes about 40

1 loaf white Pullman* bread, crust removed, sliced lengthwise into three 1-inch slices

¾ cup butter, softened

2 cups nasturtium leaves, tightly packed

Nasturtium blossoms for garnish

“Using a rolling pin, firmly roll each slice of bread to flatten. Spread each slice on one side with butter. Reserve 6 nasturtium leaves for garnish. Finely chop the rest of the leaves. Spread the chopped leaves over the buttered side of each bread slice. Then, starting from a long side, roll up each slice into a log. Wrap each log separately in plastic wrap and refrigerate until the butter has hardened, about 2 hours. (Once the butter is hard, the logs will stay rolled.) Cut the chilled logs crosswise into ¾-inch-thick slices. Arrange the slices on a platter and serve garnished with nasturtium blossoms and the reserved leaves.”

* Otherwise known as a ‘sandwich loaf’ – the name Pullman comes from their use in the cramped kitchens of Pullman railway cars. These days, most sliced bread is actually a Pullman loaf: square, and baked in a long, rectangular, lidded pan. I used some sliced rye and wheat bread I had in the freezer and lopped off the crusts.

you’re my favourite food writer…..write on.

As for the pictures, whoa!

I couldn’t agree more!

Pingback: 9 Most Popular Climbing Vegetable Plants in India - Bagicha Bazaar